Our nation’s independence came at a high human cost on all sides. We celebrate the 4th of July, which was the date in 1776 when the Second Continental Congress edited and approved the Declaration of Independence. Of course, signing did not begin until August 2nd and lasted through November.

Our nation’s independence came at a high human cost on all sides. We celebrate the 4th of July, which was the date in 1776 when the Second Continental Congress edited and approved the Declaration of Independence. Of course, signing did not begin until August 2nd and lasted through November.

On the night of April 18, 1776, Paul Revere, William Dawes and Samuel Prescott rode to warn Samuel Adams and John Hancock of their impending arrest by the British. The first shots of the Revolutionary War took place the following day at the battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775. However the soldiers fighting had about a 98% chance of survival on the battlefield, but only a 75% chance in a hospital. About 6,800 were killed in action and 6,100 wounded, yet 17,000 died of disease.

At the time of the Revolutionary War, life expectancy was only 35 years.

In 1776, only two medical schools existed in the colonies. At the time, only 1 in 9 medical practitioners had a medical degree, although none of them were licensed as licensure only existed in Europe. To educate practitioners, medical literature in America consisted of just one medical book. Most physicians had more in common with a medieval barber than a modern M.D. Much of medical treatment was based on theory and not science. The colonial medical paradigm was the Grecian theory of Humors, based on bodily fluids- blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile—and their balance. Few hospitals, with minimal supplies and contaminated food/ water, greatly contributed to the spread of disease and inadequate treatment. Medicines had previously been brought to America by ship from England, but since the Americans were fighting the British, this source was eliminated. It wasn’t until 1778 when we formed an alliance with the French that we had another supply chain. Smallpox and other viruses plagued battlefields. (It was the Revolutionary War that smallpox inoculation became widespread.)

The pioneers of modern American neurosurgery, like Sir Victor Horsley or Harvey Cushing, were not around until the mid-late 1800s. In fact, treatment of head injury was still largely based on Hippocratic concepts from ancient Greece, which included the balance of the 4 Humors.

Head injuries were a challenge to treat in the 1700s. If you were hit by a cannonball, you usually just died. But regarding man-to-man combat, the colonists primarily used muskets and not rifles, so they had to get fairly close to the British to be effective. While only about 2% of their shots were on target, they may actually have been more accurate than the British. A problem with a musket is that it used black powder, which is slow burning and a fairly weak propellant. A smoothbore musket ball was rounded lead, about 3/4th inch. These musket balls were poorly penetrable and easily deflected (conical bullets were popular until later). Soldiers could get just a welt on their skin from a weak shot, and stronger shots may penetrate the skull and lodge the ball in the brain instead of penetrating through. This more often led to seizures or infection, than immediate death. A smoothbore round would have been much more quickly lethal to the chest or abdomen, due to organ injuries less protected by bones. Death from a head shot would be slow and painful.

Many of the head injuries were scalp lacerations, concussions and skull fractures. The prevalence was so high that a field manuscript was composed by John Jones, MD, “Plain, Concise Practical Remarks on the Treatment of Wounds and Fractures”, outlining the surgical treatment of these injuries on the battlefield. Two of Dr. Jones’ non-battlefield patients included George Washington and Benjamin Franklin.

Chapter VII: Of Blows On The HeadChapter VIII: Of Injuries Arising From Concussion Or Commotion

Chapter VIII: Of Injuries Arising From Concussion Or Commotion

Chapter IX: Of Injuries Arising From A Fracture Of The Skull

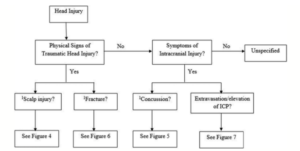

Probable algorithms can be recreated from Dr. Jones’ chapters.

Scalp Injuries

Common superficial scalp wounds were generally not treated. Larger wounds were sutured and bandaged. Wounds were sprinkled with basilicum powder or quinine, but most often whiskey. They were sometimes packed with cotton/ linen scraping and the bandages were kept damp with water or vinegar. Thesuture material was not sterile (nothing was sterile) and made from a linen thread. Infections were common as wounds routinely were washed with plain water from a bucket, and the same water was used for multiple soldiers. The purity of water could be checked with a few drops of oleum tartari. If it was pure, only a small cloud would appear. If impure, six ounces of vinegar was added to three quarts of water. However drainy pus that flowed from a wound was thought to ooze beneficially, based on the concept of Humors.

Concussions

It was recognized, even before the Revolutionary War, that brain injury did not necessarily present with signs of visible physical fracture or opening to the cranium. Medical treatment usually consisted of bleeding and purgatives (laxatives) (Just about any condition was treated with bloodletting. Even George Washington was bled about 40% of his blood volume for his epiglottitis the day before he died.) However if symptoms did not resolve, the head would be shaved to examine the skull for a missed fracture. If any irregularity was identified, a trephination may follow. The lucky soldier’s concussive symptoms would quickly resolve on their own, as the treatment of refractory signs turned a survivable injury to a deadly one.

Fractures

It was understood that a skull fracture was not in itself dangerous, but the brain was at risk from associated compression, infection or hemorrhage. A depressed skull fracture was treated with trephination (craniotomy) to decompress the brain. This often led to infection and damage to the brain while fishing out the bone fragments. There are Revolutionary War descriptions of a “fungus” growing out of a trephination for skull fracture. We now would recognize this as herniating brain tissue, but 18th century surgeons were unaware and treated incorrectly to the demise of the patient.

Trephination

Performing a craniotomy occurred in tents and on tables that were not necessarily clean. Surgeons often worked directly on the battlefield and considered the first responder. There were some formal hospitals, but scarce and unorganized since Congress was too preoccupied with other matters to pay enough attention to the needs of the medical department. Opiate pain medications existed, but there was no anesthesia. If the soldier was awake, someone would hold the head still. Fire, wood smoke, burning sulfur and exploding gunpowder were believed to preserve and restore the purity of the air. It was argued that patients who died following trephination died from the severity of their injury and not as a complication of the surgery itself. In looking at the data retrospectively, the Incans were much better at craniotomy than 18th century surgeons.

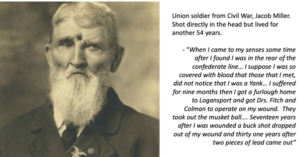

By the time of one of our next major conflicts, the Civil War, significant advances in war-time medicine developed. The principles of sanitation, hygiene, and cleaning hands/ instruments became recognized, making recovery from scalp, cranium or brain injuries far safer. Steps in disease control were initiated. The importance of smallpox vaccination was established. Rapid transport of patients to hospitals occurred. Thorough record keeping, including photographic documentation of technical advancement, disseminated medical breakthroughs. And specifically for head injury, neurosurgical techniques improved. As exemplified by Jacob Miller, a musket shot to the head was very survivable nearly a century later in the Civil War.