Watching MLB games with my sons recently, they noticed how many baseballs were seemingly thrown away haphazardly. “That ball was used once, why is the pitcher getting a new ball?” Well, that answer partly has to do with neurosurgery.

Watching MLB games with my sons recently, they noticed how many baseballs were seemingly thrown away haphazardly. “That ball was used once, why is the pitcher getting a new ball?” Well, that answer partly has to do with neurosurgery.

Nowadays, about 100-120 baseballs are used in every MLB game. (Each ball costs about $6) The average life of a professional baseball is about two pitches. And unlike tennis, where balls are circulated for a bit, once a baseball is removed from a game it never returns. Currently, the reason why the home team spends ~$720 per game on baseballs alone, is that a scuffed ball has more dynamic aerodynamics with the velocity and spin an MLB pitcher can create. However, the origin of changing baseballs goes back to the 1920s.

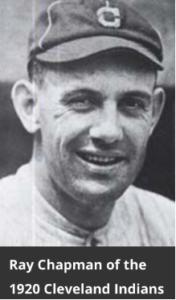

On August 16, 1920, the Yankees were playing the Cleveland Naps (now the Indians). A spitballer, Carl Mays, was on the mound and known for throwing a “submariner” pitch. This was such a side-arm throw to right-handed batters, that his knuckles occasionally scraped the dirt and the ball curved like a hyperbola back to the batter at the last minute. Mays particularly was known to be a bit of a headhunter, and even his own teammates may have hated him. However he was going for his 100th career win this day, and the following events may have contributed to him never making the Hall of Fame.

Down 3-0 in a playoff race where the Yankees were a ½ game back, Naps’ shortstop Ray Chapman came to the plate. Mays threw a high and tight fastball, and with the sound of a crack, the ball slowly rolled in front of home plate and the Yankees made the out at first. However the crack wasn’t the sound of the ball hitting the bat… it was the sound of the ball hitting Chapman’s left temple. Batting helmets would not become common until the 1940s, and hitting a batter was somewhat of gamesmanship in the 1920s. It was reported that Mays once hit Ty Cobb every at-bat in one game because Cobb threw his bat at Mays. Based on later speculation, observers claimed Chapman crowded too close, and “his head simply was in the strike zone”.

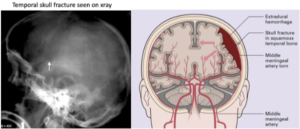

Chapman immediately lost consciousness with a gash on his head but was eventually able to take a few steps to the dugout before collapsing again. He was brought to a hospital and found during surgery, twelve hours later, to have a 3-inch temporal skull fracture. His brain was severely bruised. He died the following morning. Temporal skull fractures can be very dangerous. An artery, called the middle meningeal artery, can be injured by the fracture leading to rapid increased pressure on the brain and possible death. In modern-day, rapid transport to a hospital and CT scans diagnose this quickly, and we can offer potentially life-saving surgery. In the 1920’s delayed diagnosis would allow the hemorrhage to become so large that surgery would be futile.

Following this injury, which still to this day is the only death of a player during a baseball game, changes to the game were implemented to protect batters. For one, this game was played on a particularly foggy day. However, manipulating the balls was legal at this point. In fact, pitchers were encouraged to rub “Mississippi mud” on the balls, scratch them, and even try to misshape them to increase ball movement. In a spitball, pitchers soaked the balls in tobacco-laden saliva, making the balls dip and dive, but nearly black in color. Some argued that Chapman simply couldn’t see the dark ball in

Following this injury, which still to this day is the only death of a player during a baseball game, changes to the game were implemented to protect batters. For one, this game was played on a particularly foggy day. However, manipulating the balls was legal at this point. In fact, pitchers were encouraged to rub “Mississippi mud” on the balls, scratch them, and even try to misshape them to increase ball movement. In a spitball, pitchers soaked the balls in tobacco-laden saliva, making the balls dip and dive, but nearly black in color. Some argued that Chapman simply couldn’t see the dark ball in

the fog.

Umpires were soon urged to take any balls out of play that were not bright white. This was part of the “bean ball’ rules. And the following season, spitballs were banned. Mays later said at the end of his Hall of Fame-caliber career, “Nobody ever remembers anything about me except one thing. That a pitch I threw caused a man to die”. He always claimed it was an accident. When notified of Chapman’s death, he turned himself into to the district attorney. “It as the most regrettable incident of my career and I would give anything to undo what has happened.” Now, MLB spends about $5.5 million each season on baseballs alone.