Back in 2018 we published an introductory article on injections. However we thought we’d elaborate more with a series of blogs on the various types of injections. In Part 1 we’ll tackle epidural injections in the lumbar spine.

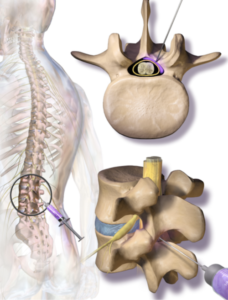

A lumbar epidural injection involves a provider inserting a needle into the epidural space and injecting a medication. Usually this is done using x-ray (fluoroscopy) to identify the target level.

Steroids

Today, the most common medication is a steroid, although it should be highlighted that even epidural steroid injections (ESI) are not Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved. Rare but serious problems have occurred after injection of corticosteroids including loss of vision, stroke, paralysis and death. Nonparticulate corticosteroids may reduce the risk of injury to the brain and spinal cord. Dexamethasone may be preferred over other steroid options.

The effectiveness and safety of ESIs have not been established, however some research has shown benefit. ESIs have been compared to placebo, with the ESI providing larger improvements in pain and disability. Evidence of both short-term (<6 months) and long-term (> 6 months) relief has been observed. In the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT), a subgroup analysis suggested the ESI are associated with a surgical avoidance rate of 41%. Other research may indicate injections may delay surgery for short-term (less than 1 year) but not long-term (greater than 1 year).

It is actually unclear how an ESI improves symptoms. The predominating hypothesis is by diminishing inflammation. While the concept seems intuitive, some human studies of lumbar radiculopathy have detected no measurable inflammatory cytokines in the epidural space. Furthermore, a 2014 New England Journal of Medicine article compared epidural steroid injections versus just lidocaine (a numbing medication). At 6 weeks, there were no significant differences between groups. Other trials have confirmed similar results. Therefore it may or may not be an “anti-inflammatory” benefit of an ESI. There could be a large placebo effect.

The known indications for ESI are radicular (leg) pain and not axial back pain. That is, pain isolated to the low back is unlikely to improve with an ESI. Pain down the leg has a better chance. Weakness and sensory deficits are less likely to improve from ESIs. Additional criteria usually include:

- Evidence of nerve root compression on MRI which correlates with the clinical findings

- Pain that has not responded to at least 4 weeks of conservative management

Of course, conservative management should include a combination of strategies to reduce inflammation, alleviate pain, and improve function. This includes physical therapy and possibly chiropractic care, acupuncture, cognitive behavioral or massage therapy. This also usually includes anti-inflammatory medications and analgesics. Documentation of compliance with a plan of therapy is helpful. Usually, about 3 months of conservative therapy is considered an adequate trial.

An ESI can be performed in many ways. Interlaminar (IL) approaches the epidural space from the posterior spine between the two vertebral lamina. The IL approach can be directly midline or slightly off-midline. Using a slightly off-midline (parasagittal interlaminar) technique may allow better spread of injectant to more spinal levels compared to midline. Pain relief seems to be better at 6 months too. Often, lumbar IL injections can migrate about 2 levels above and 1-2 levels below. The IL approach is considered capable of delivering the medication closest to the assumed site of pathology. A transforaminal (TF) approach delivers medication through the intervertebral foramen. The TF approach is generally preferred because delivery of the injectant at the involved nerve root maximizes injectant concentration at the site of pathology. Compared to interlaminar, it is the most “target-specific”. Moreover, the injectate can be delivered to the anterior epidural space. A positive correlation has been reported between fluid injection volume into the epidural space and relief of radicular leg pain.

Another slight variation on this is a selective nerve root block (SNRB), in which the injection needle remains outside the intervertebral foramen, in contrast to a TF ESI in which the needle tip is within the foramen. The difference between SNRB and TFESI is simply the final needle position. SNRBs require lower injectant volumes (0.5 – 0.6 mL) to reduce inadvertent spread to other roots and therefore really isolates a specific nerve. It is better as a diagnostic option for consideration of surgery, rather than a therapeutic intent. TF injections use higher volumes (1-4 mL) and the injectant can still reach other levels. TF injections have more opportunity to be therapeutic.

A caudal ESI enters through the sacral hiatus at the sacral canal. Caudal ESI require relatively large volumes and are the least specific injection. However it is considered the safest and easiest approach. It may be the preferred modality in postsurgery syndrome. Large randomized controlled trials show evidence of similar pain relief from all three approaches (IL, TF and caudal).

A caudal ESI enters through the sacral hiatus at the sacral canal. Caudal ESI require relatively large volumes and are the least specific injection. However it is considered the safest and easiest approach. It may be the preferred modality in postsurgery syndrome. Large randomized controlled trials show evidence of similar pain relief from all three approaches (IL, TF and caudal).

Following an ESI, a pain diary is important. Pain diaries are a critical component of tracking pain fluctuations, including changes before and after procedures. Reliance of self-report measures on recall of past pain can lead to reliability problems, since current pain significantly influences memory for past pain. There is nothing indelibly specific about the mark pain leaves on our hippocampus.

The immediate and delayed pain response(s) could have diagnostic implications, as well as treatment predictive value, and represents a powerful tool for patient selection or planning. The immediate response to an epidural injection likely reflects the reaction to the anesthetic, while a delayed response may be to the steroid. The anesthetic portion serves as a diagnostic block, and pain elimination is usually interpreted as accurate targeting of the pain generator. The local anesthetic may have action on the epidural, neural or perineural pain generator’s immediate nerve supply. In patients without an immediate or delayed improvement, the anesthetic may not have come in direct contact with the injectant, or the pain generator may be different from the area targeted. In patients with a partial immediate response, there may be more than one pain generator, with only part of the pain problem being exposed to the anesthetic. In patients with no immediate response, but a positive delayed improvement, again the pain generator may be resistant to the local anesthetic, may not be in contact with the local anesthetic, or the delayed response showed improved pain from a systemic steroid reaction.

For an ESI to be considered successful, there should be at least a 50% sustained improvement, using the same scale, for at least three months. If a patient fails to respond well to the initial ESI, a repeat ESI after 14 days can be performed using a different approach, level and/or medication. We used to limit the number of ESIs per year, however repetition may be more regulated by the amount of steroid used and actual response. However there are long-term risks to steroids.

ESIs are not intended to disintegrate a disc herniation, per se. Their benefit, not matter what modality, is to improve symptoms while the body naturally heals itself. Disc herniations can resorb on their own. Other pathologies compressing nerves can improve.

Regenerative therapies

Regenerative therapies usually are described in the context of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and stem cells. Neither is FDA approved, but both are deemed more investigational than steroids.

PRP does not contain stem cells, and is derived from the patient’s blood. The final concentration of platelets, leukocytes and growth factors varies between and within different formulation techniques, as well as between and within patients. Epidural PRP has been compared to steroids in a 2021 study, and while both showed improvements in pain, there was no statistical difference. There is no substantive evidence that PRP is superior to other epidural injections. There is no proof of regeneration. However it is clear that PRP often bears substantially higher cost, less uniformity, and far less research basis.

Stems cells have not been directly compared to epidural steroid injections. Similar to PRP, there may be improvement, but without any superiority of stem cells or proof of tissue regeneration. The financial cost is high. Long term complications, including tumor formation, has been associated with stem cells and discussed in our prior blogs.

Conclusion

Lumbar ESIs are a reasonable interventional option for leg pain failing other conservative trials. They are not indicated for everyone with pain. Primarily, steroids are used. Regenerative therapies are becoming more popular, but with high cost and lack of proven superiority yet. Probably related to the exorbitant out-of-pocket costs they bear, there’s a huge incentive to advertise scruplelessly.

Tracking the response to an injection is critical. Many patients claim the pain returned and therefore deem this a failure. While this may be true, tracking the actual pain changes with a diary may show a diagnostic indication that simply did not become therapeutic.

Injections are unlikely to be permanent in-and-of themselves. They may simply improve pain and function while the body heals itself. They may be a diagnostic preview, to support more invasive treatments later. They may be repeated in certain scenarios. But most importantly, failure of epidural injections does not necessarily mean surgery is the next step. Failure of an injection may indicate surgical conversations may commence. However failure of an injection may also predict surgery will not be helpful either.

Failure of a prior injection does not necessarily predict a response to current symptoms. The spinal pathology may be completely different, and therefore a new injection may benefit a new structural change. A chronic spine issue may not have previously been responsive, but now susceptible.

It may be similar to going to revisiting a previously frequented restaurant for dinner. The chicken may have been poorly seasoned and non-satiating last year, but tonight it may just hit the right spot… As Anton Ego said in Ratatouille, “Last night, I experience something new, an extraordinary meal from a singularly unexpected source.”