Part 1 of this series discussed lumbar epidural steroid injections (ESI). These injections are primarily reserved as a diagnostic workup of radicular (leg) pain, or as a therapeutic modality when noninvasive treatments have failed. Evidence of nerve root compression should be seen on advanced imaging like a MRI, correlating with the clinical findings.

Isolated low back pain is an exclusion for ESI.

Back pain is a very complex symptom. It is one of the most common musculoskeletal diseases, and 45-75% of patients report feeling pain persistently 12 months after its onset. Low back pain persisting > 3 months is termed “chronic”.

Although opioid analgesics are commonly requested by patients and sometimes offered by providers, their clinical benefit in the treatment of chronic low back pain remains uncertain. There is no evidence to support long-term use of any dose of opioid for treatment of back pain.

Between 80-90% of low back pain patients complain of non-specific low back pain, meaning the underlying pain-causing factors are not yet determined. Many lumbar spine structures could be a cause of pain, including the disc, facet joints, bone muscles, tendons, ligaments, fascia, synovium, joint capsule, etc… All of these structures are supplied a certain type of nerve (thin myelinated A- delta fibers). However, not all pain is carried by A-delta fibers, or even slower C fibers, and some pain is a consequence of emotional, cognitive and behavioral elements. This partly explains the poor correlation with MRI findings and symptoms, and why interventions with no effect on the spine structure (psychological therapy or acupuncture) can improve pain yet some interventions like surgery do not help at all.

Unfortunately, we have no proven injections for disc-generated pain (discogenic pain). Some evidence supports a procedure called “discoblock”, but this is usually reserved for predicting benefit from surgery. Regenerative therapies like intradiscal stem cells are investigational and not fully proven. DiscGenics is a biopharmaceutical company who recently published some two-year data, however the results are still preliminary and not replicated. Some interventions work for myofascial pains, such as trigger point injections (dry needling is different and does not inject any substance). Again, regenerative therapies like PRP for muscle pain is not proven. A newer procedure called Intracept, may be an option for bone-pain (vertebrogenic), but there is limited experience with this technique. Cognitive-behavioral therapy is recommended for nociplastic pain. However for facet-mediated back pain, we have some options.

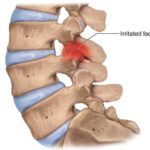

There are few conditions in interventional pain medicine as controversial as lumbar facet joint pain. The diagnosis of lumbar facet joint pain relies on the combination of symptomatology, physical examination, sometimes imaging, and diagnostic block.

The prevalence of facetogenic pain is less than 15% in the non-elderly, yet there was about a 131% increase in facet-directed interventions between 2007 and 2016. This mismatch between the known prevalence of symptoms and procedure utilization suggests confusion on the recommended guidelines for this therapy.

Facet-mediated pain is usually best with walking or sitting, and worse with extension and rotation. Pain that is not predominantly in the midline, and over the facet joints, could be an indicator. On exam, tenderness overlying the facet joints, and pain exacerbated with extension/ rotation could be facetogenic. Symptoms radiating down the leg are less common.

On imaging, facet enlargement or the development of effusions/ cysts may suggest a pain generator. However not all facet pain shows imaging changes, and imaging alone cannot predict pain 100% of the time.

When facetogenic pain is suspected, just as with radicular (leg) pain, conservative management is still the initial option. Physical therapy, chiropractic care, acupuncture, massage therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy are recommended. Anti-inflammatories may be beneficial.

However with failure of conservative options, pain at least 3 months’ duration, with at least 3 out of 10 intensity and an inability to perform at least two activities of daily living, facet-mediated interventions may be considered.

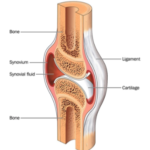

The concept is that anesthetizing the numerous pain components to the facet joint may improve symptoms. The lumbar facet joint is a true synovial joint (just like a knee), and pain generation could be from multiple areas including the synovial membrane, hyaline cartilage surface, subchondral bone, periosteum, and/or ligaments.

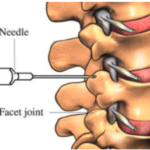

Historically, both intra-articular (IA) injections and diagnostic medial branch blocks (MBB) were considered.

Historically, both intra-articular (IA) injections and diagnostic medial branch blocks (MBB) were considered.

An IA injection into the facet joint capsule only addresses the synovium, leaving other possible pain generators with nociceptive fibers unattended. For example, the injectant confined to the capsule could not reach the surround ligaments. Therefore, an intra-articular injection is no longer preferred, and really only considered in rare patients and those which also harbor a synovial cyst.

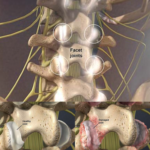

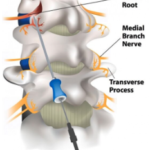

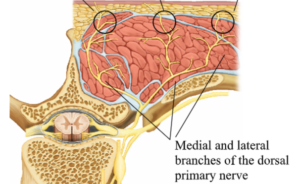

Currently, MBBs are preferred. The medial branch of the spinal nerve (just a small branch) facilitates sensory transmission from all the components of the synovial joint.

A MBB is usually best performed in two separate stages, called dual-comparative-blocks. An initial injection is performed with a local anesthetic, and then pain response is followed. Steroids are not recommended for use in a MBB. Each lumbar facet joint is innervated by two different medial branches, usually being the branch from the level above and the target level.

To truly be accurate, 100% pain relief should be observed for the duration of the anesthetic, however some suggest at least an 80% improvement is sufficient. This being said, using anything but a 100% cut-off may raise uncertainty of placebo response or another unidentified pain source. The pain relief really needs to be concordant, meaning the exact type of pain of which the patient originally was complaining. This will be short-lived. Lidocaine only really works for about 1 ½ to 2 hours. Bupivacaine should last a bit longer, closer to 2 ½ to 3 hours. If the pain relief lasts longer than the known duration of anesthetic, this should be considered a failure and likely placebo-response. Some patients think that when the pain returns after a couple hours, the injection failed… however that is exactly what was supposed to happen. If a positive response occurred with the initial injection, a 2nd injection may be performed on a different day using a different duration anesthetic, but in the exact same location. If the pain response is again concordant, and in-line with this different duration, then the trial is thought to be positive and the pain may be from that facet joint.

To truly be accurate, 100% pain relief should be observed for the duration of the anesthetic, however some suggest at least an 80% improvement is sufficient. This being said, using anything but a 100% cut-off may raise uncertainty of placebo response or another unidentified pain source. The pain relief really needs to be concordant, meaning the exact type of pain of which the patient originally was complaining. This will be short-lived. Lidocaine only really works for about 1 ½ to 2 hours. Bupivacaine should last a bit longer, closer to 2 ½ to 3 hours. If the pain relief lasts longer than the known duration of anesthetic, this should be considered a failure and likely placebo-response. Some patients think that when the pain returns after a couple hours, the injection failed… however that is exactly what was supposed to happen. If a positive response occurred with the initial injection, a 2nd injection may be performed on a different day using a different duration anesthetic, but in the exact same location. If the pain response is again concordant, and in-line with this different duration, then the trial is thought to be positive and the pain may be from that facet joint.

Diagnostic MBBs should be performed at no more than two bilateral levels or three unilateral levels per session. That equates to injections covering no more than two spinal levels.

The next consideration following a dual-comparative-block is radiofrequency ablation (RFA). In the exact same spot as the dual MBBs, an electrode “burns’ those small medial branch nerves. (Patients with pacemakers cannot undergo the procedure due to the interaction of the radiofrequency signal and their cardiac device.) Again, the procedure does not burn the main nerve, but just the small medial branch.

This can provide a more long-lasting interruption of sensory transmission from that lumbar facet. Unfortunately the medial branch can regrow, so the procedure may need to be repeated in 6 months if at least 50% pain improvement was achieved. Again, a successful RFA is thought to improve pain by just 50%. This raises the question of exactly what a MBB or RFA is really doing. Why two MBBs, ideally achieving 100% pain relief could result in a RFA just alleviating 50% of the pain, is perplexing. If the MBB trial was accurate, and correctly diagnosed the facet as the pain generator, then one would think the RFA also should also nearly guarantee 100% relief. But this is the problem with pain injections, and why there is such controversy. Pain is subjective and the placebo-response is powerful. As such some literature argues for completely skipping MBB and going straight to RFA, due to elevated costs in a paradigm including MBB, and the inexactness of MBB predictability. But as of now, the dual MBB path to RFA is the standard protocol, and likely provides the best odds of successful RFA.

This can provide a more long-lasting interruption of sensory transmission from that lumbar facet. Unfortunately the medial branch can regrow, so the procedure may need to be repeated in 6 months if at least 50% pain improvement was achieved. Again, a successful RFA is thought to improve pain by just 50%. This raises the question of exactly what a MBB or RFA is really doing. Why two MBBs, ideally achieving 100% pain relief could result in a RFA just alleviating 50% of the pain, is perplexing. If the MBB trial was accurate, and correctly diagnosed the facet as the pain generator, then one would think the RFA also should also nearly guarantee 100% relief. But this is the problem with pain injections, and why there is such controversy. Pain is subjective and the placebo-response is powerful. As such some literature argues for completely skipping MBB and going straight to RFA, due to elevated costs in a paradigm including MBB, and the inexactness of MBB predictability. But as of now, the dual MBB path to RFA is the standard protocol, and likely provides the best odds of successful RFA.

The MBB to RFA protocol is usually not considered an option to delay spinal surgery, as an ESI may for radicular symptoms. Facetogenic pain, in and of itself, is not a good indication for lumbar decompression, lumbar fusion or lumbar artificial disc.

One issue with repeating RFA involves the other function of the medial branch nerve… providing some motor innervation to the lumbar paraspinal muscles.

Therefore the risk of RFA, and greater likelihood following numerous RFAs, is weakening of the paraspinal muscles leading to more pain and loss of structural integrity. Therefore young patients who are athletes may wish to avoid RFA. And at some point, repeat RFAs should be abandoned if more permanent relief is not achieved. Of course, if despite repeat RFAs, the pain continues to recur, the patient should consider different options either for more permanent fix or exploration of a different pain generator.

Conclusion

Lumbar MBB on a path to RFA is a reasonable option for axial back pain with the combination of symptomatology, physical examination, and sometimes imaging, indicating facetogenic pain.

Some providers attempt to suggest no symptom, exam or imaging finding can predict the facet as a source of pain. This is ridiculous. If any provider offers any intervention, whether medication, injection, surgery, etc… without any reason to think it will work, then a second opinion is probably warranted.

Understanding the steps in diagnosing facetogenic pain is important, since the initial diagnostic injections are not expected to last more than a couple hours. Even RFA is not known to be permanent.

However facetogenic interventions may be helpful for the carefully selected patient.

Failure of a facet-directed injection does not necessarily mean surgery is indicated. Failure of these injections may just mean the pain generators is not yet identified and a more prudent analysis is warranted. Facetogenic pain is not necessarily a good indication for any spine surgery.