Injuries are a natural part of sports, and back pain is not uncommon.

A very specific back problem, spondylolysis, has been linked to athletics. A sports injury may initially begin as a stress reaction, then progress to a fracture of the pars interarticularis, which is the part of the bone connecting to the facet joints. This fracture is called a “spondylolysis”. This pars interarticularis fracture can lead to one vertebra slipping over another, called spondylolisthesis. (Spondylolysis refers to the fracture, while spondylolisthesis refers to the slippage). It should be noted that we commonly discuss spondylolisthesis also as a degenerative or arthritic spine problem in adults.

Lumbar spondylolysis can cause progressive low back pain in the athlete, exacerbated by extension or twisting. There may be lumbar hyperlordosis leading to the appearance of excessive abdominal convexity.

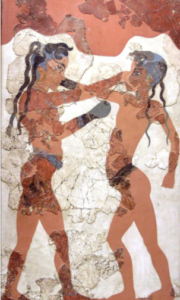

In 1967, excavators discovered some Bronze Age wall paintings from the 17th-16th century BCE. The “Boxing Boys” fresco was discovered in the Akrotiri settlement of Thera, now known as Santorini.

This painting demonstrates a boy on the right with a hyperlordotic curve, prominent abdomen, and forward displacement of the spine, indicative of spondylolysis. This suggests spondylolysis in sports has been observed for centuries. In this particular style of boxing, the 8-10-year-old boys have a glove on only one hand, allowing the other hand to grip the opponent, likely resulting in repeated arching of the low back which could lead to the spondylolysis. Some may argue this fresco could represent an artist’s imaginative accentuating style, however, the boy on the left seems to be accurately rendered with prepubertal anatomy. Potentially more telling, the loin belt is sloped to the pelvis on the deformed boy, which would be an expected finding from the pelvic parameters associated with spondylolisthesis. Lastly, Thera was an island to itself and seemingly isolated from the eastern Mediterranean culture. The artist likely would have painted directly from observed life, and been uninfluenced from any other artistic movements. (The Greeks at the time paid attention to idealizing the human body in the likeness of the Gods, avoiding deformity). This suggests a lack of abstractness in the piece, and the artists attempt to portray the true appearance of the boys.

This painting demonstrates a boy on the right with a hyperlordotic curve, prominent abdomen, and forward displacement of the spine, indicative of spondylolysis. This suggests spondylolysis in sports has been observed for centuries. In this particular style of boxing, the 8-10-year-old boys have a glove on only one hand, allowing the other hand to grip the opponent, likely resulting in repeated arching of the low back which could lead to the spondylolysis. Some may argue this fresco could represent an artist’s imaginative accentuating style, however, the boy on the left seems to be accurately rendered with prepubertal anatomy. Potentially more telling, the loin belt is sloped to the pelvis on the deformed boy, which would be an expected finding from the pelvic parameters associated with spondylolisthesis. Lastly, Thera was an island to itself and seemingly isolated from the eastern Mediterranean culture. The artist likely would have painted directly from observed life, and been uninfluenced from any other artistic movements. (The Greeks at the time paid attention to idealizing the human body in the likeness of the Gods, avoiding deformity). This suggests a lack of abstractness in the piece, and the artists attempt to portray the true appearance of the boys.

There are no ancient texts that refer to spondylolisthesis, and no other artistic illustrations exhibiting this shape, other than the “Boxing Boys”. This may indicate that our medical predecessors did not consider this an actual disorder, but possibly a natural variant of children’s appearance in sports.

About 4.4% of 6 year-olds are found to have spondylolysis, which is thought to be the peak age onset. At this point in development, bones have a thinner cortex and their growth plates are weaker. Of the kids with subsequent spondylolisthesis, about 93% were engaged in vigorous sports at the onset of pain. Of note, it seems that injury may be associated with “unaccustomed loads”. Children good at a particular sport are more likely to be injured by playing a sport to which they are unaccustomed. Adults do not seem to have this problem. Although we rarely image babies and their spines are more cartilaginous, spondylolysis has never been found in a newborn, suggesting this may not be a congenital disorder. The mechanism is thought to be physical overuse with recurrent and strenuous twisting and lumbar hyperextension leading to recurrent microtrauma.

Spondylolysis is found in hockey, tennis, diving, volleyball, gymnastics, rugby, and football.

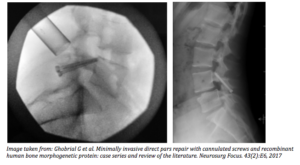

Modern treatment of symptomatic spondylolysis is initially conservative, stopping the sporting activity to allow healing. About 90% of patients can return to baseline activity within 6 months. Bracing may be used to try and help the fracture heal, but there are varying results. Surgery is an option, although we try to avoid operating on young athletes. Some newer minimally invasive techniques place screws through the fracture, pulling the fracture ends together, and allowing healing. This approach may be best performed tubular minimally invasively, which is modified from techniques attempted since the 1970s, to avoid destabilizing the ligaments and joints, which could contribute to failed surgery and non-healing. This surgical technique is different from the traditional fusion (even minimally invasive fusion) of two vertebral bodies together which could limit some range of motion, becoming a bigger obstacle for the young athlete compared to the average adult.