Chronic low back pain is a spectrum of different types of pain. Studies have indicated that 60% of people with low back pain will continue to have pain or frequent recurrences one year after onset. Persistent pain is a consequence of complex interactions of biological, psychological, and social factors. Furthermore, about 85% of these cases do not have a specific physiological cause, making the development of effective treatments and pathways to recovery challenging. As such, the International Association for the Study of Pain defines pain as, “an experience”. A Brain MRI may be more helpful for some chronic back pain, continue reading below to find out more.

The key component is that “pain” can be distinct from “nociception”, which is the nervous system’s process of encoding painful stimuli. In nociception from a disc herniation, for example, the disc presses on part of the nerve root (dorsal root ganglion), sometimes causing inflammation, which in turn may produce a signal that travels to the spinal cord and eventually the brain. However, there is a completely separate system of emotional and cognitive elements influencing the response to pain, which is why there is often a poor correlation between spine MRI findings and symptoms. Furthermore, this explains why interventions like psychological therapies, “mindfulness”, or even acupuncture can have profound effects on pain, yet have no direct effect on the spine or nerves. Chronic pain may not always be a purely sensory-dependent process.

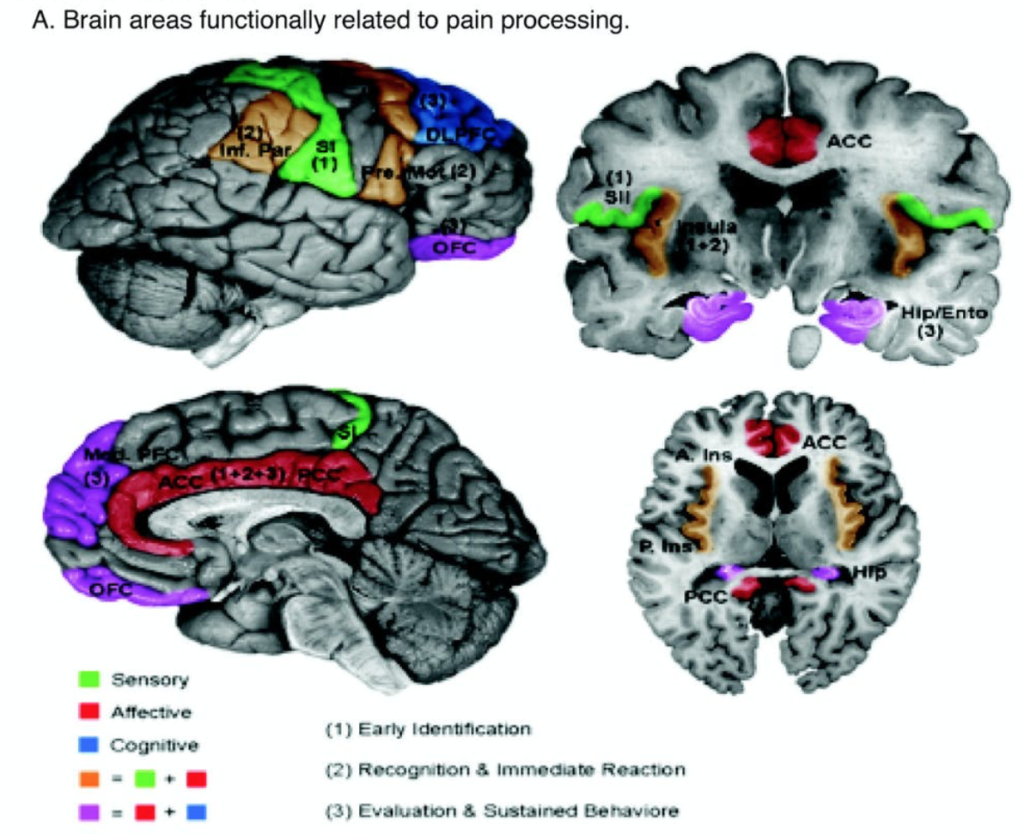

Recent pain studies using MRI suggest a network of brain regions, not lumbar MRI findings, referred to as the “pain matrix”. They combine the 3 dimensions of pain: being sensory, emotional, and cognitive components. The sensory component, or nociceptive part, is where nerves send signals from the painful nerve root to the brain cortex, called the somatosensory area. The emotional/ affective component is the cingulate and limbic regions when influencing the unpleasantness of pain and influence mood. (Some patients with excellent coping and euphoric moods do not complain of pain.) Finally, the cognitive areas are in the frontal and parietal regions, which assess the degree of attention directed on pain, and interprets the meaning of the overall pain experience. (Some patients who divert their attention have reduced pain intensity.)

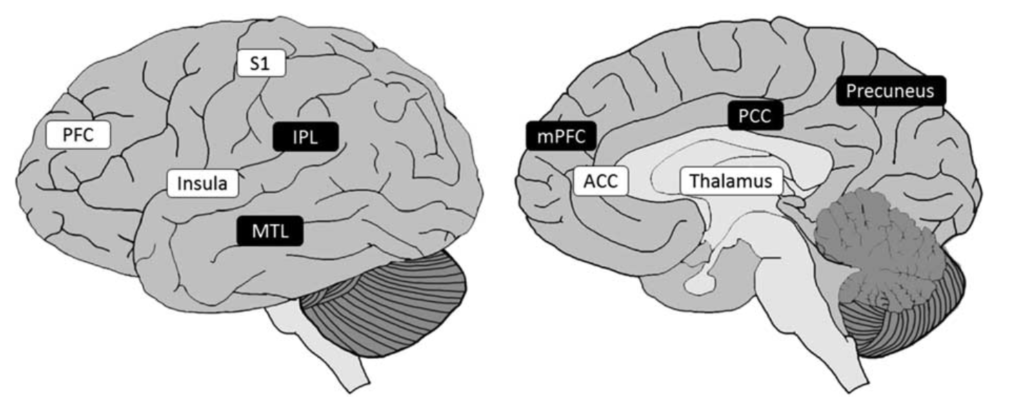

A recent study assessed about 715 articles about chronic pain and brain imaging. In chronic pain patients, there are decreased regional gray matter volumes in the prefrontal cortex, insula, temporal lobes, thalamus, cingulum, and pre- postcentral regions, compared to non-pain patients. White matter volumes also appear to be decreased in the corpus callosum and internal capsule.

Of great interest, in functional MRI studies, chronic spine pain patients do not seem to show significant differences in brain activity during spontaneous pain, although they do have lower pain thresholds compared to non-pain patients. More simply said, when spontaneous pain is experienced by a chronic pain patient, the noxious brain tracts are not overly active, suggesting their chronic pain is not a nociceptive process. Instead, the chronic pain groups have alterations in their emotional and cognitive regions.

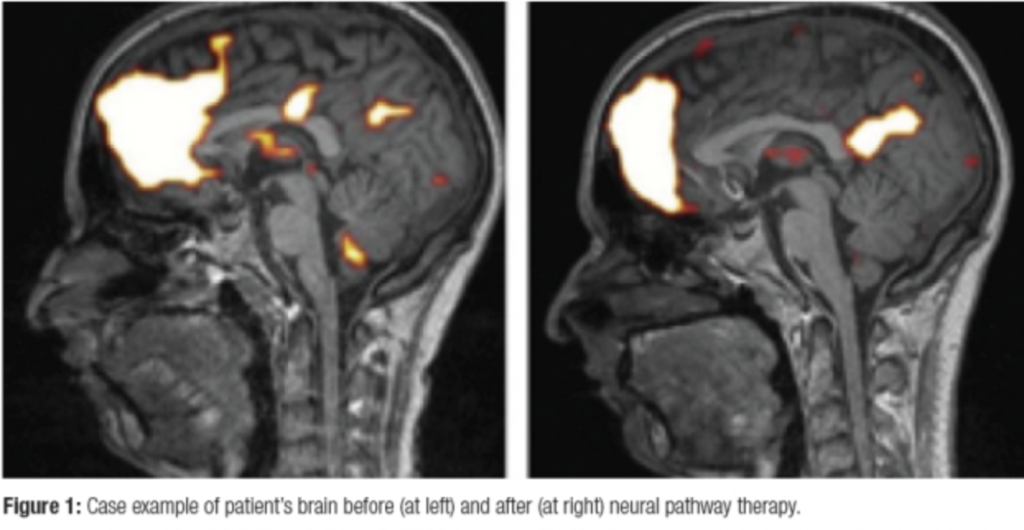

In other studies, after undergoing various treatment strategies for chronic pain (psychological and cognitive strategies), functional and structural brain abnormalities were reversible when the pain was eliminated.

In summary, the solution to chronic pain in some patients may not be a surgical spine procedure. Treating chronic degenerative arthritis may not solve symptoms, however, this does not mean there’s no hope. Alternative pain management strategies may appropriately address the emotional and cognitive aspects, leading to significant relief without a surgical back scar.